- PREFACE

- NEWS

- ≪仮寓にて At the Ephemeral Dwelling≫

- Primary Days

- Grass Town

- Private China

- Destiny

- RIDES

- Visions of Trees/Photosynthesis

- Amanohashidatezu Invert Ekkenkan View and Chindanotaki Falls, Fuji Miho Seikennji Temple Painting View juxtaposition of the actual Painting

- Series:New Homelands of the Novels Yu-hui 新・小説のふるさと 『由煕』

- CV

- BIOGRAPHY

- CONTACT

- PREFACE

- NEWS

- ≪仮寓にて At the Ephemeral Dwelling≫

- Primary Days

- Grass Town

- Private China

- Destiny

- RIDES

- Visions of Trees/Photosynthesis

- Amanohashidatezu Invert Ekkenkan View and Chindanotaki Falls, Fuji Miho Seikennji Temple Painting View juxtaposition of the actual Painting

- Series:New Homelands of the Novels Yu-hui 新・小説のふるさと 『由煕』

- CV

- BIOGRAPHY

- CONTACT

New Homeland of Novels

新・小説のふるさと

「新・小説のふるさと」では、小説のゆかりの地を訪ねて、その世界を写真で表すことを試みました。

現実から小説を見返せば物語の奥深さを体感したり、主人公の思いに改めて気づいたりすることもあります。

小説の読み方は人それぞれですが、これもまた一つの読み方かなと思っています。

なぜ、「新」とついているかというと、偉大な写真家、林忠彦の「小説のふるさと」へのオマージュとしてこのシリーズを始めたからです。

このシリーズは月刊誌『中央公論』に連載され、そこで取り上げた四十三冊の小説はすべて平成に刊行されたものです。

In "Shin Shosetsu Furusato" (Homeland of New Novels), I attempted to visit the places associated with novels and capture their worlds through photography.

Looking back at novels from the perspective of reality can help one experience the depth of the story or become aware once again of the protagonist's feelings.

The way we read novels varies from person to person, and I think this is also one way of reading.

The reason for the "New" is that it is an homage to the great photographer Tadayoshi Hayashi's series "Shosetsu no Furusato" (Homeland of Novels), which I started.

This series was serialized in the monthly magazine "Chuokoron" (中央公論), and the forty-three novels featured there were all published during the Heisei era.

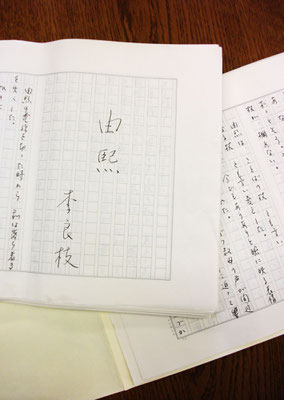

•『由煕』 Yuhi (jap. 由熙, ユヒ, kor. 유희) 李良枝 平成元年 講談社刊

あらすじ

在日韓国人の李由煕が「私」と叔母の住むソウルの家に下宿を始めて半年。由煕は留学先のS大学を中退し、日本に帰る飛行機に乗ってしまった。 由煕は「私」に茶封筒に入った紙の束を残していた。そこには「私」の読めない日本語が何百枚にもわたって書き連ねられている。 なぜ彼女は韓国での大学卒業を果たせなかったのか。「私」から見ると、言語学を専攻しているにしては不確かな発音で、文法も初歩的な間違いが目立つ。試験やレポートのため以外、ハングルの読み書きをしていない。そしてウリナラ(母国)を愛することができな い、とハングル文字を書いた夜の由煕を思い出す。 姉妹のように親しくなったはずが、由煕と理解しあえないまま去られてしまった「私」の戸惑いが描かれる。

*あらすじは中央公論による

Synopsis:

Lee Yu-hui, a Korean living in Japan, has been lodging at the house in Seoul where "I" and my aunt live for six months. Yu-hui dropped out of S University where she was studying abroad and boarded a plane back to Japan. She left behind a bundle of papers in a tea envelope for "me". Those papers are filled with hundreds of pages of Japanese characters that "I" cannot read.

"Why couldn't she graduate from a university in Korea?" From "my" perspective, her pronunciation is uncertain for someone majoring in linguistics, and basic grammatical errors are noticeable. Apart from exams and reports, she does not read or write Hangul (Korean alphabet). And I recall the night when Yu-hui wrote in Hangul characters that she cannot love her homeland. Despite becoming as close as sisters, the confusion of "me" is depicted as Yu-hui leaves without mutual understanding.

*Synopsis by Chuokoron.

エッセイ Essay

ソウルの出版社に行く用事ができた。その際、李良枝ゆかりの場所に行きたいと伝えたら、ヤンジの妹の栄さんからこんなメールをいただいた。

「姉の住んでいた住所です。姉のお友達のファジャさんから以前聞いていた情報も添えておきます。

良枝オンニは、考子洞(ひょじゃどん)という所にいた際にアラーキー(荒木経惟)も訪問して屋上で写真をとってもらい、木蓮の花がいっぱいあった。ミンジャさんと同居した最後の家。光化門の裏の方よ。近くに土俗村(토속촌 삼계탕)というサムゲタンのおいしいお店があり、そこへお客さんを連れて行ってた…」

仁川には午後四時ごろに着いた。少し蒸し暑い5月のはじめ、空港から高速鉄道でソウル市内の鍾路区の安宿についたのは五時半過ぎだった。昌徳宮はすぐのところにあった。あらかじめ地図で調べてあった孝子洞へも30分もあればたどり着けるのではないかと思った。夕暮れが迫っていたが、あまり写りの良くないコンパクトカメラをぶら下げて夕方の街に出た。

僕は李良枝と直接会ったことはなかった。リービ英雄さんに彼女のことを聞き、著作を読み、ふとしたきっかけで妹の栄さんと知り合いになった。ある時、李良枝の書棚がまだ残っているのを知った。李良枝が亡くなった時、彼女のお父さんが大久保のマンションの屋上に李良枝コーナーをつくり、そこにそっくり移した書棚があるとのことだった。栄さんにそれを撮りたいと言ったら、彼女は快諾してくれた。そしてその撮影の時に僕は初めて李良枝の片鱗に触れた。

>>>>>>>>>>

李良枝コーナーは六畳間ほどのプレハブ造りの部屋で、その日階段を上るとコーナーのカギはもう開かれていた。強い意志が美しさの中に見える李良枝のポートレート。何枚もの記念写真が祭壇のように並べられた正面の脇に書棚が並ぶ。父はよくここに来てお酒を汲んだと栄さんは言った。そして毎年命日にはかつての友人たちが集うという。

六棹ほどの書棚だった。一月の中旬とは思えないほど日差しは暖かかった。新大久保の喧騒も6Fのこの部屋まで聞こえてこない。左の壁にかかる巫俗と僧舞の長い袖の衣装。カマーゴさん(栄さん)が灯していった線香の煙がつぅーと立ち上る。その煙を乱さぬように、もう一度書棚に目をやって、撮影の準備を始めた。ポールを設営する。雲台を正確に組む。配線をカメラからコンピューターに回して、遠隔で一棚ずつ撮り始める。哲学書が目について、堅い本が多いなと思った。三木清の文庫本を丁寧に切り取ってノートに貼り、一ページずつ感想を記したノートもあった。

「音楽でもかけて、好きにしてね」と栄さんに言われていたが、この静けさを乱すのが勿体ないような気がしていた。東側の書棚の端には小さなCDプレーヤーがあった。入っていたCDはコロンビアの音楽だった。これは栄さんのものだ。テープの方を見てみると小さなハングル文字で何かが書いてある。思い切ってスイッチを入れると、笛と太鼓のゆったりしたリズムが聞こえてきた。巫俗の音楽だろうか。これが李良枝の聞いていた音なのかしら。その音色に、静寂だった空間が場面を変えたように息吹いた。そうだこれを聞きながら撮ってゆこう。そう思った。

西日が差し込んでくる。午後の時間が過ぎようとしていた。ペースを上げて次々と棚を移動し、カメラの位置を調整する。垂直・水平・ねじれを確認してシャッターを切る一連の作業を何度も繰り返した。何十回目かの時に見えづらかったモニターの角度をグイと変えた。反射を拾って一瞬ぎらりと光った後、矢を放たれたような視線に射すくめられた。それはたまたま李良枝の写真の眼が鏡面となったモニターの画面に反射したからだった。胡笛(ホジュク)のすすり泣き。揺鈴。杖鼓の拍子。衣擦れの音。視線の正体はわかっているのに、それを感じるたびに僕はどきりとした。

書棚をほぼ撮り終えた頃、栄さんが屋上に来た。僕はテープを止めて、彼女にそれを差し出した。黙って彼女はそれを見た後、姉のテープだと言った。書いてある文字の意味を尋ねると、「キ、キ…ボン、基本だね」と彼女は言った。

後片付けをして、その祭壇のある書棚の部屋から夕暮れの屋上に出た。視線の話に「姉も踊っていたんだわ。お姉ちゃんまた来るね」と言って栄さんはコーナーのドアを閉めた。

>>>>>>>>>>

韓国の出版社の用事で一日がつぶれ、その翌日は書棚の撮影の参考にとチェックを見に美術館や記念館を回った。北村韓屋村(북촌한옥마을)で作家と値段の交渉をして現代の冊架図(책가도)を二枚、買った。時間が飛ぶように過ぎていく。そして三日目にようやくまた元下宿を訪ねていった。

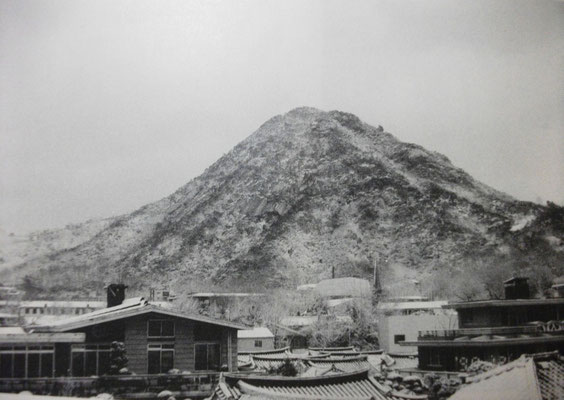

洗濯物干しもない屋上はかなり広かった。そこから青瓦台の屋根がちょっと見えた。下に見える民家は新しくなっていたが、目の前にある山は李良枝が撮った写真の山そのもので、ある一点に立つと全く同じ角度から同じ絵が見えた。李良枝もこの同じ場所に立って北岳山を撮ったのだと思った。

大久保の屋上で射すくめらた、視線の主は、この屋上でも舞を舞ったことがあると後で知った。李良枝はサルプリの踊り手でもあった。

The Yangji Lee Corner was a prefab room about six tatami mats in size. That day, the door was already unlocked when I climbed the stairs. There was a portrait of Yangji, in which her strong will seemed to radiate from within her beauty. Several commemorative photos were arranged like a shrine. To the side, her bookshelf stood in quiet dignity. Sakae told me that their father often came to this space to drink, and that friends gathered here on the anniversary of Yangji’s death each year.

The bookshelf consisted of six sections. Despite it being mid-January, the sunlight felt unusually warm. Even the noise from the bustling streets of Shin-Okubo didn’t reach this quiet sixth-floor rooftop. On the left wall hung long-sleeved garments used in shamanistic rituals and monk dances. The smoke from incense, which Camargo-san (Sakae)had lit earlier, rose slowly, as if it didn’t want to disturb the space. I cast another look at the bookshelf and prepared for the shoot, careful not to disrupt the tranquility. I set up the poles, assembled the tripod head precisely, and connected the camera to the computer for remote shooting, capturing one section at a time.

>>>>>>>>>>

The bookshelves were filled mostly with dense philosophy texts, and I noticed many scholarly works. One notebook contained excerpts from essays by Kiyoshi Miki, carefully cut and pasted into the pages, along with Yangji’s personal thoughts on each section.

Sakae told me, “Feel free to put on some music,” but I couldn’t bring myself to disrupt the silence. There was a small CD player at the end of the eastern bookshelf. The CD inside featured music from Colombia, which belonged to Sakae. Curious, I looked at the tapes nearby. One had small Hangul characters written on it. When I gathered the courage to press play, I heard the soft rhythms of flutes and drums. Perhaps it was shamanistic music. Could this have been the music Yangji once listened to? The moment the sounds began, the stillness of the space seemed to shift, as if it had come alive. I decided then to listen to it as I continued photographing.

The afternoon sun poured in, signaling that the day was coming to an end. I moved quickly from one section to another, carefully adjusting the camera's position. I repeatedly checked for vertical alignment, horizontality, and any tilt before taking each shot. After dozens of adjustments, I bent the monitor to reduce glare. For a moment, a sudden reflection from the screen glinted like an arrow—and in that instant, I felt as though I had been pinned down by a gaze. It was the reflection of Yangji’s portrait caught on the monitor.

The wail of the hojok flute, the rhythm of janggu drums, the rustling of robes—though I knew the source of the gaze, it startled me every time.

Just as I finished photographing the bookshelf, Sakae came up to the rooftop. I stopped the tape and handed it to her. She looked at it silently and then said, “This was my sister’s tape.” When I asked what the words on it meant, she read them aloud: “Gi… Gi-bon... Basic, that’s what it says.”

After packing up, I stepped out onto the rooftop. Sakae, closing the door to the bookshelf room, said with a smile, “My sister used to dance here, too. I’ll come again, Onee-chan(Sis).”

>>>>>>>>>>

I spent the next day at the publisher, and it took up most of my time. The following day, I visited museums and memorial halls to gather ideas for the bookshelf project. In Bukchon Hanok Village (북촌한옥마을), I negotiated with an artist and purchased two contemporary chaekgado (책가도) paintings. Time seemed to fly by. On the third day, I finally returned to Yangji’s former boarding house.

The rooftop was surprisingly spacious, without even a clothesline in sight. From there, I could just catch a glimpse of the Blue House’s roof. Although the houses below had been renovated, the mountain view was exactly the same as in Yangji’s photograph. Standing in the same spot, I saw the same view from the same angle that she must have captured.

Later, I learned that the piercing gaze I felt on the Okubo rooftop belonged to someone who had once danced there. Yangji had also been a performer of the salpuri dance.