- PREFACE

- NEWS

- Press Release Book Shelves Retrospective

- Primary Days

- Grass Town

- Private China

- Destiny

- RIDES

- Visions of Trees/Photosynthesis

- Amanohashidatezu Invert Ekkenkan View

- Creases and Vectors on Sesshu Gardens

- Series:New Homelands of the Novels Yu-hui 新・小説のふるさと 『由煕』

- Memorial: Takashi Tachibana's Bookshelf Exhibition 追悼 立花隆の書棚展スライド再録

- CV

- BIOGRAPHY

- CONTACT

- PREFACE

- NEWS

- Press Release Book Shelves Retrospective

- Primary Days

- Grass Town

- Private China

- Destiny

- RIDES

- Visions of Trees/Photosynthesis

- Amanohashidatezu Invert Ekkenkan View

- Creases and Vectors on Sesshu Gardens

- Series:New Homelands of the Novels Yu-hui 新・小説のふるさと 『由煕』

- Memorial: Takashi Tachibana's Bookshelf Exhibition 追悼 立花隆の書棚展スライド再録

- CV

- BIOGRAPHY

- CONTACT

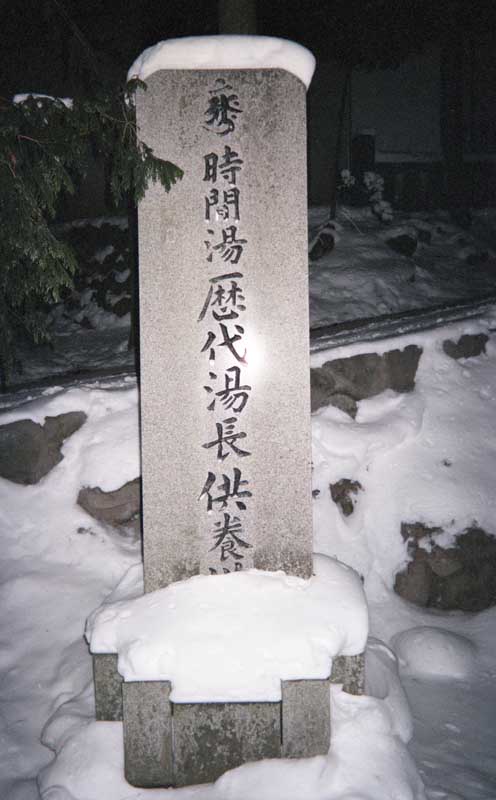

Grass Town

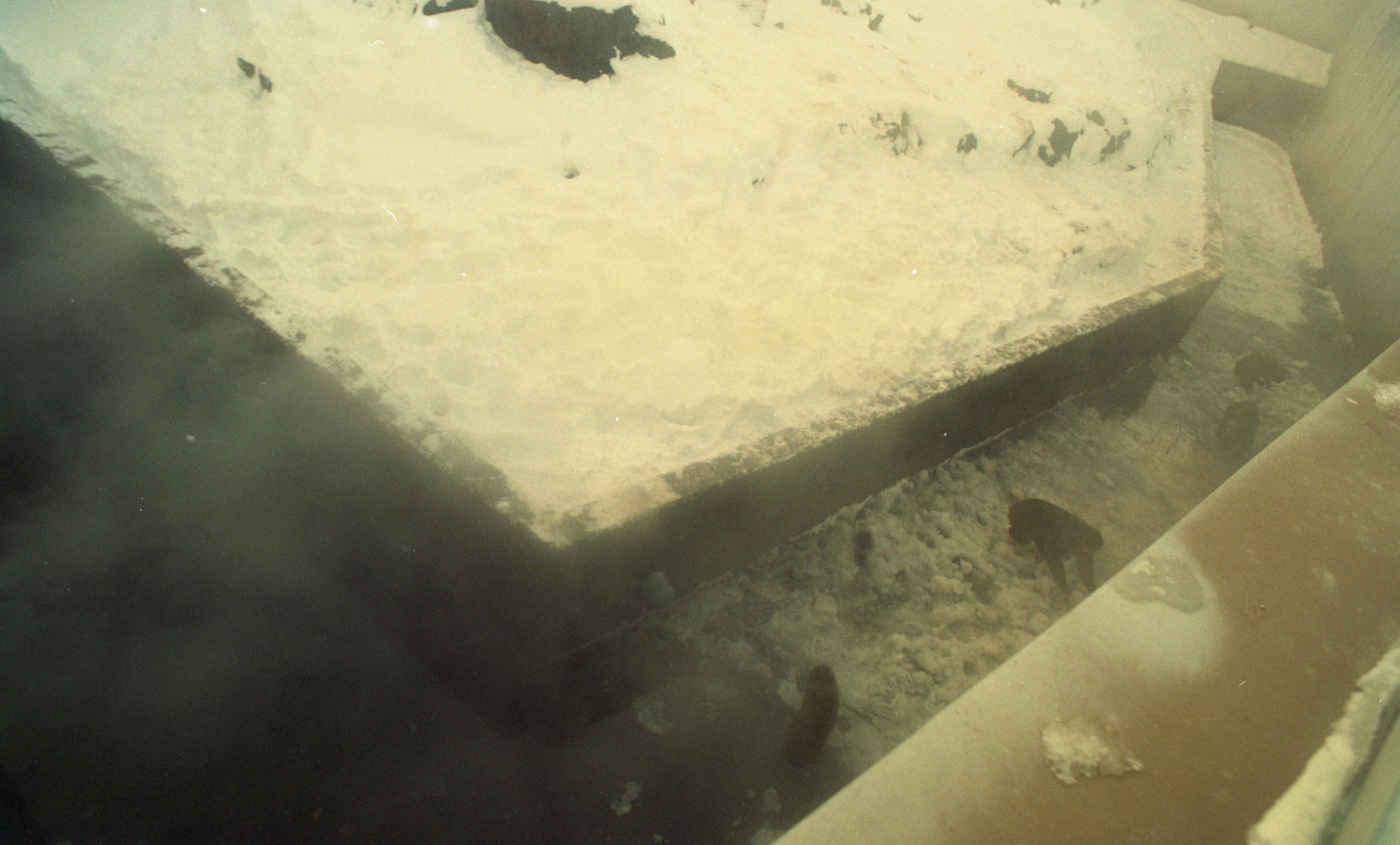

連絡駅から山道をのぼり、いくつかの谷を行くと、ナトリウムランプの橙色と水蒸気の中に忽然と浮かぶ街を見る。Grass Townだ。

路地は入り組み、ここに迷うといくつもの共同浴場にぶつかる。鼻を刺す硫黄分のにおいが、否が応でも興味を引き、やおら浴場の戸をガラリとあけて、自然と熱い湯に身を浸してしまうのだ。行基が魅了され、徳川将軍が湯を汲み、庶民から病人まで、ありとあらゆる人が誘蛾灯のように煌めく街に吸い込まれてきた。

湯の「はしご」という700年以上も前からの遊戯の中で、「Grass Townの人は無愛想だ」と湯につかった湯治客が言う。「サービスがない」と誰かが話しかける。だが、それでもここにやってきて、木張りの浴場の床にゆったりと横になる。湯につかり、食べ、路地をさまよいながら次の浴場へと向かう。そして何かを発見する。そこには巨大な湯畑や格式を示した宿がある。温泉饅頭はうまい。一風変わった動植物園では猛毒の蛇がとぐろを巻き、全時代的なドギツイ演出の猿回しがある。高温の湯に、湯長という指導者のもと、何度も入浴する荒々しい入浴法も残っている。ハンセン病施設の歴史、湯長との会話、救われた病人の話、Grass Townを世界に知らしめたお雇い外国人医師たちの銅像も。

気がつけば、昼夜を問わず、湯と路地をさまよい、何かを発見したり、ぼうっとしたりしている。住人は踏み込まず、踏み込ませず。客は崇められもしないが、疎まれもしない。その微妙な距離感が、さまようことを許してくれる。客人をもてなすところはたくさんある。だが、「さまよう」遊戯があるところはここにしかない。

ここは田舎ではない。その煌びやかな光と強烈なエンターテイメントもさることながら、匿名でさまよえる「湯のシティ」なのだ。

明治期の英語のパンフレットを見つけた。そこには、日本有数の湯量が喧伝され、温泉の優れた効能が書かれ、美しい自然と湯に遊ぶ日本で一番人気の温泉として紹介されていた。そしてそこには、「草津 Grass Town」とあった。

Climbing up a mountain path from the station and passing through several valleys, you suddenly see a town floating in the glow of sodium lamps and steam. This is Grass Town.

The streets are a maze, and if you lose your way, you inevitably stumble upon one of the many communal baths. The pungent smell of sulfur pricks your nose, stirring your curiosity. You find yourself opening the creaky bathhouse door and naturally slipping into the steaming hot water. Enchanted by this place, monks like Gyōki, shoguns from the Tokugawa era, and people of all walks of life, from the sick to the ordinary, have been drawn to this town, like moths to a flame.

Bath-hopping, an activity that has existed for over 700 years, is a signature pastime here. A bather mutters, "The people of Grass Town aren’t exactly welcoming." Someone else chimes in, "There’s no service here." Yet even so, visitors keep coming back, lying down on the wooden floors of the bathhouses, soaking in the water, eating, and wandering from one alley to another in search of the next bathhouse. Along the way, they discover something new: a massive hot-spring field, inns exuding historic grandeur, or the simple delight of freshly made onsen manju (steamed buns). There's also an unusual zoo where venomous snakes coil menacingly, and a throwback to a bygone era—a garish monkey show with theatrical flair. The rugged bathing method of repeatedly immersing oneself in scalding water under the guidance of a bath leader, or yuchō, still survives here. The town’s history of leprosy treatment, conversations with the bath leaders, stories of those healed by the waters, and statues of foreign doctors who introduced Grass Town to the world all add to its mystique.

Before you know it, day and night merge into a continuous cycle of wandering between baths and alleys, discovering new sights or simply drifting into a state of quiet observation. Residents neither intrude nor allow others to intrude. Guests are neither revered nor shunned. This subtle balance creates a unique space where wandering becomes an act of leisure. While there are countless places that welcome guests, there’s only one where aimless wandering is part of the experience.

This is no countryside. It’s a “City of Hot Springs.” Its dazzling lights and bold entertainments are remarkable, but even more so is the anonymity it offers—a place where you can roam freely and lose yourself in the “Hot Spring City.”

I came across an English pamphlet from the Meiji period. It boasted of Japan’s abundant hot springs, their exceptional health benefits, and the beautiful natural surroundings, introducing Grass Town as one of Japan’s most popular hot spring resorts. There it was: “Kusatsu – Grass Town.”